“You see, I had this space suit. How it happened was this way.”

Science fiction readers will instantly recognize the opening lines from Robert Heinlein’s 1958 Scribner juvenile novel, Have Spacesuit, Will Travel. The narrator, small-town teenager Kip Russell, wins a used spacesuit as fourth prize in a soap jingle contest, setting off a chain of events that takes him as far as the Lesser Magellanic Cloud.

I never went that far. But, you see, I do have this space suit.

Aside from the joy any Heinlein fan would find in owning a spacesuit, it’s really not that big a deal. Unlike Kip’s suit, mine never went into space. Nor is my spacesuit suitable for extra-vehicular activity; it’s strictly for inside use. Besides, it doesn’t even have a helmet. Cosmonaut suits from the former Soviet Union in far better shape (not to mention helmets) sell for less than you’d think. The rubber on my suit is rotten, the fabric is torn, and there are razor blade slashes all over it. But I’m pretty sure this is the only Apollo suit in private hands.

The pencil marks on the faded tag hanging from the suit read: “Apollo #7 Prototype, SPD-143-3 011, Med Reg.”

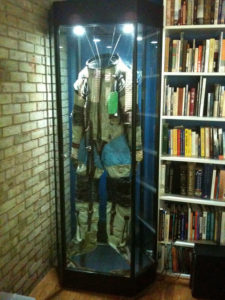

My spacesuit in its case in my office. Apollo 7, the first manned Apollo mission, was an 11-day Earth orbital, notable as the first manned launch of the Saturn 1B, and mostly served as a test for the redesigned command service module. It was the only spaceflight for two of the astronauts, and the final flight for Wally Schirra, the only man to fly in Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. So, this could be Wally Schirra’s spacesuit, but it could also belong to Donn Eisele or Walter Cunningham, the other crewmembers. It could also have belonged to one of the backup crew members, Thomas Stafford, John Young, or Eugene Cernan. (They ended up flying the Apollo 10 mission.)

Apollo 7, the first manned Apollo mission, was an 11-day Earth orbital, notable as the first manned launch of the Saturn 1B, and mostly served as a test for the redesigned command service module. It was the only spaceflight for two of the astronauts, and the final flight for Wally Schirra, the only man to fly in Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. So, this could be Wally Schirra’s spacesuit, but it could also belong to Donn Eisele or Walter Cunningham, the other crewmembers. It could also have belonged to one of the backup crew members, Thomas Stafford, John Young, or Eugene Cernan. (They ended up flying the Apollo 10 mission.)

Because an Apollo mission required years of preparation, each astronaut received six spacesuits, enough to take care of accidents, modifications, and wear and tear. One of the six would go on the mission; the rest ended up in a big pile in a warehouse somewhere in Florida. And one day, someone at NASA decided it was time to clean up the warehouse. If you’re looking to get rid of a few hundred used spacesuits, there aren’t a lot of places you can send them. There are rules about this sort of thing. So, they decided to “donate” the suits to the National Air and Space Museum, where I happened to be working.

In late 1973, I had moved from North Carolina to Washington, DC, for a job as a research assistant in the Division of Aeronautics of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. The famous building on the mall was just starting construction; the museum (such as it was) occupied its old quarters in the Arts and Industries Building, the red brick structure next door to the Smithsonian Castle. (It’s under renovation after having been essentially condemned as unfit for human habitation; a sentiment shared by many of the building’s residents — one of whom who used to refer to it as the “National Roach and Rat Museum.”) We also had a tin shed out back, a Quonset hut that had once housed the engineering group that designed the Liberty engine.

I did research jobs for the curators, catalogued archival materials (unrolling hundreds of aircraft blueprints and piling stuff on them to keep them flat), straightened files, and supervised student interns. And, of course, I worked the warehouses.

There was a rule that said no artifact could be moved without the presence of a “member of the curatorial staff.” As I was the most junior person who could be called that, I spent a fair amount of time at our network of warehouses. We were in the old Torpedo Factory in Alexandria (now a collection of artists’ studios), in a warehouse on Lamont Street in a moderately bad part of town, and in our Suitland facility, then known as Silver Hill and now as the Garber Facility.

After the Torpedo Factory collection had been consolidated and moved, Lamont Street was next. While as a “member of the curatorial staff,” my official job was to supervise, but in a practical world, I got a quick course in driving a truck and a forklift, and along with a couple of our laborers, started packing up and moving stuff out to Silver Hill. I complained about it after a few weeks, so my boss got someone in another department to take over. However, that guy pulled the wrong lever on the forklift and crushed a pile of valuable model aircraft against the roof of the truck, meaning I got the job back a week later.

One afternoon, I pulled up at the loading dock to find another truck pulling out, and there were several pallet loads of spacesuits. Two museum technicians were pulling out the ones in best shape, and hanging them on a rolling coat rack. Because these suits had never been in space, they were going to be a research collection rather than a display one—source material for someone’s future Ph.D. dissertation on the evolution of spacesuit design. Those suits (40 or 50) ended up in a meat locker at Silver Hill, where they remain until this day. As far as the rest were concerned, that’s where the razor blades came in. The suits not selected for the research collection were slashed (selling them was a no-no for a variety of technical reasons) so they could be marked as “destroyed and disposed of,” and then thrown into the dumpster.

Once it was in the dumpster, it was fair game. “Mind if one of those suits follows me home?” I asked the chief tech of the warehouse.

He laughed and said sure. “Don’t sell it,” he added — as if I would.

Unlike Kip, who named his suit “Oscar,” I never named mine, nor have I ever worn it; I’m too tall. I worked for one astronaut, Apollo 11 command module pilot Mike Collins, who directed the National Air and Space Museum, and during my years there met several others — they were all surprisingly short — I rather expected them to be giants in size as well as in spirit.

The suit has followed me around for many years, and as a part of restoring my house, I asked my sister-in-law and decorator Elisa Dobson to figure out some way to display the suit. She found a case and figured out a way to support the suit, and now at long last it’s in my office (right).

I’ve picked up a few interesting souvenirs in my life, but this one is my very favorite. After all, how many people can claim a Heinlein title for their very own?

I was, of course, also a fan of the TV series, Have Gun—Will Travel, and I’m thinking about changing my business cards to match.

Have Spacesuit — Will Travel

Email Dobson

Washington